Where can you fly 100 or even 200 XC kilometres? What should I bear in mind? What equipment should you have with you? What skills should you have to fly such distances? How can I plan routes? What tools will help me to find the next thermal in flight? Questions upon questions, which I get to the bottom of in an interview with Ulrich Scheller, an experienced cross-country pilot.

Ad Nubes: What is cross-country flying for you? What is the fascination for you?

Ulrich: That’s a good question, flying in itself is fascinating, the fact that you can take to the air at all with such a small paraglider out of a rucksack, I think that’s amazing in itself. And what particularly fascinates me is the fact that you can keep going for longer and longer without a motor, that you can actually fly almost all day. And that you can see things that you would otherwise never see.

Ad Nubes: I’m sure freedom also has a certain significance for you? That you can practically choose the routes you want to fly, without any major restrictions.

Ulrich: Exactly, definitely. Freedom is incredibly important to me. Flying itself is the greatest freedom you can imagine. I don’t think anyone on foot has ever felt such a sense of freedom. And of course you are also responsible for the consequences. Of course you have certain restrictions, but the freedom of movement and the possibilities you have are incredible.

Ad Nubes: So how important is flying compared to other hobbies you might have?

Ulrich: I haven’t had many other hobbies in recent years, partly due to family and work. Flying definitely has the highest priority, otherwise I wouldn’t even manage to be in the right place on the right days.

Ad Nubes: But flying must be a relatively high priority for you, how do you manage the practicalities of balancing your family and flying?

Ulrich: Yes, it does work. It’s not always easy, of course, because there are many things in life, but that’s probably the case for everyone. And catching the good flying days is very important to me. That’s why I usually manage it.

Ad Nubes: Are your wife and son tolerant enough to give you the freedom you need to fly regularly?

Ulrich: Yes, they do. And my wife has realised that my mood also depends on whether I get to fly.

Skills

Ad Nubes: What would you say are the skills you need to have to be a successful cross-country pilot?

Ulrich: There are a lot of basics, of course, but I don’t think the training is that exciting, so I won’t start there. What was definitely very important for me was the step of moving away from the local mountain and landing site. That was a really big point. Yes, the skills. Let me think… There are thousands of things you can think about. Of course, you have to be familiar with your equipment, you have to have the confidence to do things like that, to perhaps fly into a stronger thermal, to even fly downwind. In order to fly really far and fast, you have to be able to centre yourself properly, find the updrafts, read the terrain, understand where it is likely to go up, where are the places I’d better avoid. And then it’s ultimately about finding the most effective line. And planning the day optimally. So the question is always, what exactly do I want to achieve? If I want to fly a 50 kilometre triangle, then I plan it completely differently than if I want to get as far as possible. You have to use the whole day to fly 250 kilometres. It’s not so much about completing a certain distance, but simply getting the maximum out of it in all respects. And for such long distances, I don’t plan the route in advance, but rather I set myself the times so that I know I can fly in one direction until such and such a time, then I have to turn around. And I plan about the whole day for that.

Ad Nubes: We’ll come back to planning later. What helps you to be a good cross-country pilot outside of flying? I also listened to your podcast with Lucian, where I also talked about analysis skills. How important is that in flying?

Ulrich: That’s difficult to answer. All the work on the thermal map certainly helps me. And firstly, because I have it in flight, of course. So I fly with the thermal map and also simply because I’ve done a lot of work with it. I’ve seen where the thermals are for many areas. The map showed when someone had found thermals somewhere. That was certainly an advantage. Beyond that, I don’t know if the analytical ability helped me much because there are different types of pilots who have become successful pilots with very different predispositions.

Ad Nubes: How long was your longest flight so far?

Ulrich: The longest was this year from the Staller Sattel, 242 kilometres, in around 10:30 hours, so mental fitness is also an important factor.

Ad Nubes: Definitely yes. Mental and physical fitness is important. My longest flight so far was 5 hours 15 minutes and I was pretty exhausted. Did you only fly one day or did you fly again the next day?

Ulrich: It was just one day and it’s exhausting every time. It’s the typical tour in South Tyrol, where I usually drive there the evening before, spend the night in the car and then walk up the mountain and then there’s the flight, which is hopefully very long. So I’m definitely exhausted after a day like that. But you can train for it. I’ve noticed that I can now fly for much longer without feeling exhausted. In the beginning, I was also exhausted after 2 to 3 hours. Then it slowly got better and now I can keep going for 10 to 11 hours, even though it’s exhausting of course.

Ad Nubes: And the strongest thermal time doesn’t start until maybe 13:00 and you need full concentration, which makes things even more complicated. But is it feasible for you to still be fully concentrated after 3 to 4 hours of flying, then for the strongest thermals?

Ulrich: Yes, obviously, I can manage these long flights. Of course it’s exhausting, but 3 to 4 hours isn’t that long for me because I’ve had a lot of longer flights over the last few years. The body gets used to it enormously and for me it actually gets exhausting towards 6 to 7 hours, where I realise that it’s really been a lot now. When you’ve been on the road for so long, you’re motivated enough to keep going.

Ad Nubes: On the subject of safety training, do you do regular safety training?

Ulrich: I actually did far too little of it. I have done 2 safety training sessions in my flying time, which is quite little and I know that I have deficits in this area. That’s also one of the reasons why I haven’t flown a two-liner yet or why I haven’t moved up the classes so quickly.

Ad Nubes: Do you do training for yourself, e.g. travelling to Kössen and taking a training day to practise steep spirals, wingovers and the like yourself?

Ulrich: Well, wingovers and spiral dives, yes. But I wouldn’t dare to just fly the full stall or something like that. That’s one thing I’m still missing and where I need to catch up.

Ad Nubes: You fly the UP Trango, which is a C-wing?

Ulrich: It’s just a 2.5-line wing, not a 2-line wing. And the wing has been very successful this season.

Ad Nubes: You will continue to fly the wing for the time being?

Ulrich: I’ll keep flying it for now. Of course I’ll look at everything that comes onto the market, but at the moment I’m very happy with it.

Route planning

Ad Nubes: Right, let’s talk about route planning. How do you plan your routes?

Ulrich: I now know a lot of routes by heart, but in the beginning I mainly look at other people’s routes. Typically, I go to the XContest or DHV-XC, take a look at it on the map and also in Google Earth to see where exactly it was flown. I’m interested in the parts of the route that I don’t know yet. In a new area, I would have to look at a lot. At the moment, when I’m mostly flying in familiar areas, it’s still mostly small unknown sections. And then I look at what routes someone is flying, where exactly they have found thermals, which ridge they are flying to. This allows me to see if there are any regularities, where you can expect difficulties, etc…

Ad Nubes: XContest and Google Earth are the tools you use to plan your route. Do you write down the findings from them or do you just keep them in your head?

Ulrich: I keep it in my head.

Ad Nubes: There are tools like ThermiXC, for example. You can set waypoints and plan the route relatively precisely. But you don’t save the route in XC-Track, you really fly by memory?

Ulrich: I use ThermiXC because I can see where the FAI sector is and how far I have to fly to have a reference point. I do this more often when I realise that there is a difficulty on the route. For example, if we have a lot of westerly wind and might not be able to cross over Sterzing. Then I would lay out the route again and see how far I have to fly so that it still fits into the FAI sector. However, I don’t programme this as a waypoint on my device but keep it in my head.

Ad Nubes: Of course, it’s also possible that you’ll crash early. Do you also look at existing mountain railways, available take-off points or public transport so that you can get back to your car as quickly as possible or do you fly off at random?

Ulrich: Rather by chance, so of course I now have a few ideas about where the roads are, where public transport might be available. That’s the experience of many years. But I don’t usually have a look at it beforehand because it’s also relatively unclear where exactly you’ll end up and the routes have become quite long, so it’s usually not that helpful to have a look everywhere beforehand.

Ad Nubes: OK and the airspaces, do you look at them beforehand?

Ulrich: Yes, if there’s a situation somewhere where you come close to airspaces. In particular, of course, I keep my eyes open for anything new. I rarely fly in such areas, so the airspace around Innsbruck, for example, is always a story like that. You always fly very close to the CTR there. Recently on the Gaisberg it was also a difficult story with the Salzburg airspace, as you only have a very small area in which you are allowed to fly. But the advantage is that I also have this on the device. XCTrack shows the airspaces in flight and that is extremely important to me.

Ad Nubes: When you do your planning with Google Earth, for example, or look at it in advance, do you also look for emergency landing areas?

Ulrich: Yes, definitely. It’s important for me to know that there’s always something in the glide angle range and I don’t just want the very small clearing, so it has to be a bit more. Sometimes I watch videos, for example Dimi uploaded one recently. In Ticino, where I think to myself, there’s nothing left to land. That gives me a queasy feeling. In the areas where I normally fly, it’s no problem at all. Emergency landing sites must always be available for me.

Ad Nubes: Do you have any routes that you could recommend for us? Let’s start with routes that are over 100 kilometres. Do you have any recommendations for those who want to fly 100 kilometres for the first time?

Ulrich: As an FAI triangle or a flat one?

Ad Nubes: Both.

Ulrich: So for a flat triangle, the easiest 100 kilometres is probably the Pinzgauer Spaziergang. It’s also quite well-known. I’ve never started from the Schmittenhöhe, but I think that would be the easiest because you get out relatively early and only have to fly up and down the Pinzgau. My first hundred was from Kössen, and I think it’s a very nice circuit and in my eyes it’s not that difficult. Kössen first in the direction of Hochkönig. So Saalfelden, Steinernes Meer and then via Zell am See back through Pinzgau and then northwards. The one important thing in Kössen is that you immediately fly to the south side and don’t wait until the valley wind comes up. Then you can fly beautiful routes from there.

Ad Nubes: And what about the Karwendel triangle, have you ever flown it?

Ulrich: I’ve flown it once. And yes, the Karwendel is certainly quite a nice circuit, but then you have the airspace problem. You have to understand that and call the band announcement to know whether the airspace is open. There are also days when this works very well. However, I am less familiar with the area because I now live further away.

Ad Nubes: Astro Control now also offers this service. You can check on their website whether the relevant airspace is free, whether the TRA is active or, alternatively, you can call them. What else would you recommend? Do you have 100 kilometres more in store?

Ulrich: You can also start the whole thing from Hochfelln. This is the typical Hochfelln tour and it also includes the Pinzgau. There is the difficulty that the Steinplatte is a big jump. But otherwise it’s a very nice circuit, especially because there are usually lots of pilots on the way and that helps enormously when you’re flying your first hundred.

Ad Nubes: I find it very complicated. The topology is not clearly defined. In Kössen it’s relatively clear where you have to fly, but the mountains around Hochfelln are very rugged and don’t have a clear structure. It’s quite complicated for me to fly there.

Ulrich: On a good day there are I don’t know, 30 to 40 pilots and you can just fly behind them.

Ad Nubes: Try it when you get the chance.

Ulrich: It’s difficult, but most or the longest routes in Germany are flown from the Hochfelln.

Ad Nubes: Do you have any more 100 kilometres that you could recommend?

Ulrich: There are so many possibilities.

Ad Nubes: Alright, that’s enough, that had been 4 or 5 routes now.

Ulrich: Where it generally gets easier is in the high mountains. In South Tyrol, that would also be more like a two-hundred metre route. You can do a lot more there. You can start much earlier, the thermals are stronger and if you fly along a long mountain range, such as the Pustertal or Defereggental, you can quickly cover many kilometres.

Ad Nubes: From the Grente, for example, you say the Defereggen Valley heading east and back again. Towards Sterzing means west and back towards the Dolomites and then back towards Grente.

Ulrich: Exactly, that’s the standard triangle from the Grente. Also one of the best to fly, beautiful. Of course, you have to be prepared to run up there. You also have to be able and willing to fly for a long time. Those who are prepared to do so will probably get a long way.

Ad Nubes: And the Speikboden?

Ulrich: The Speikboden is also a good mountain, but you can only start a little later than from the Grente and are not immediately on the race course. You have to cross the valley first, so there is a slight disadvantage. For someone who doesn’t want to run up, it’s still very good and you can still fly 200 kilometres quite well if you extend all sides of the triangle far enough.

Ad Nubes: I find it complicated from Speikboden, as there is a valley crossing directly in front of you. You first have to fly south and with a B glider, for example, you need at least 3000 metres take-off altitude.

Ulrich: No, you’ll be fine with less. With 2700 metres you should be fine. And if you have an altitude of 3000 metres at take-off, then you can basically fly directly along the ridge to the west. And later traverse in the very high mountains. Some people have already done this, and it could be much faster. But you run the risk of not making it and then getting stuck on the north side. That would be a big problem to get on. But with an altitude of 3000 metres right after the start, it should work.

Ad Nubes: What kind of 200 kilometre routes are there here in the Northern Alps? What would you recommend there or what is feasible for the average Ottonor pilot?

Ulrich: Well, it’s difficult to generalise for the average pilot, I would say that the average pilot doesn’t fly 200 kilometres. But if someone tries it and is already one of the better pilots, the typical round is from Hochfelln. This is also a German flight, which goes from the Hochfelln almost all the way back into the Zillertal. Then along the whole of Pinzgau via Zell am See, possibly into the Gastein Valley and back again as far as possible. Another thing that always fascinated me was the tour from the Zillertal. People have already flown 300 kilometres from the Zillertaler Höhenstraße. But I’ve never tried that myself.

Ad Nubes: How do you fly it?

Ulrich: The triangle was first flown in a south-westerly direction, first along the ridge towards the Brenner Pass. Then back to the far north, i.e. over Kössen.

And then basically the Kössen triangle in a much larger form to the rear of Bad Gastein and back in Pinzgau on the south side.

Ad Nubes: Have you ever flown the glacier triangle?

Ulrich: I’ve never tried it from Brauneck before. Generally speaking, I haven’t travelled much in the area and it just didn’t happen when I lived in Munich. Now it’s further away and logistically it’s more complicated. It’s usually the case that if it flies well from Brauneck, then it also flies quite well from the Chiemgau Alps.

Ad Nubes: What about Bassano for you, it’s a relatively easy area to fly cross-country, are you travelling there often?

Ulrich: Yes, I am. And Bassano is actually a great route for a flat hundred. It’s hard to find anywhere else that’s so easy and so safe.

Ad Nubes: Dimi made a very good video. It’s a really top video that he made and is also highly recommended, anyone who is interested in flying 100 kilometres there should watch the video.

Equipment

Ad Nubes: Let’s move on to the next topic of equipment. What instruments do you have with you?

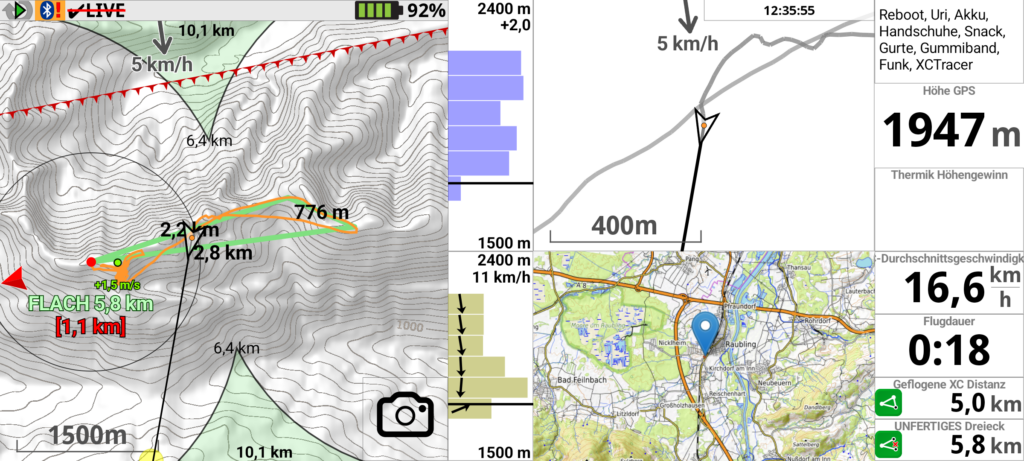

Ulrich: I have 2 things. My normal mobile phone, a Google Pixel 8, and next to it the XC Tracer Maxx II.

Ad Nubes: It has a display. So I only fly with my smartphone and the XC Tracer without a display. Why do you think a display makes sense?

Ulrich: I used to fly like that too, with the smaller XC-Tracer and then I gradually added more and more XC-Track. In the end, the screen was relatively full. Then I switched to the XC-Tracer Maxx, also to get many displays over to the other screen. This freed up space on the mobile phone. The thermal map has taken up a lot of space and I don’t want to switch between several screens. My XCTrack is configured so that everything is on one screen. Then I don’t have to switch anything in flight and I don’t have to look for which value is where.

Ad Nubes: Do you fly with the thermal assistant?

Ulrich: I have 3 different maps on it. One is the normal XC map, then the thermal assistant and then my self-programmed thermal map integrated as a website. And all of them together take up a lot of space.

Ad Nubes: We’ll come back to the thermal map in detail later. We’ve already mentioned your wing. You’ve also mentioned the vario, what kind of harness do you fly?

Ulrich: The Niviuk Arrow.

Ad Nubes: I’ve also been flying it recently, I really like it. What was your point, why did you buy it?

Ulrich: Similar to the glider, I tried out different ones. I didn’t see too many options on the market. I wanted one that was relatively light. It had to be aerodynamic and comfortable for long distances. The Niviuk Arrow is very good according to these criteria. Before that I flew the Lightness 3, which is smaller and lighter but also more wobbly.

Ad Nubes: And it was already very comfortable, but I feel even more comfortable in the Niviuk Arrow now because it’s simply quieter. That was also what convinced me. Food, what do you take with you?

Ulrich: Firstly, the large hydration bladder with water. I typically fill it up completely because I need a bit more in terms of weight anyway. And then, depending on how long I expect the flight to be, I take something to eat with me. I used to always have muesli bars, but now I prefer to take a normal bread roll or something that you can still eat on the flight. Maybe a pretzel or something. That’s about it.

Ad Nubes: What do you have with you for emergencies?

Ulrich: Do you mean emergencies in the sense of accidents?

Ad Nubes: Yes, a first aid kit or something like that.

Ulrich: Not even that much. I’ve got a tree rescue kit in there now, but apart from that I don’t really have anything for emergencies.

Ad Nubes: I’ve recently seen that you also publish videos. Do you now fly with a video camera or is that an exception?

Ulrich: I bought the old video camera (Insta 360 X2) from Dimi and got a bracket to mount it on. I’ll be flying and making videos with it more often, but not professionally. I just do it for fun.

Ad Nubes: You also take nice photos of yourself and the area, do you do that with your smartphone or do you have another camera with you?

Ulrich: A normal smartphone. On my phone it works well with a double click on a button. And then click, click, click, quickly take 5 photos. I have to edit them later so that they’re not skewed and look decent. A nice reminder for me and sometimes for other people too.

Weather

Ad Nubes: On the subject of weather. What do you use for the weather forecast? Which tools can you recommend?

Ulrich: The tool I pay for is XC Therm. That’s the most important source for me. That’s what I mainly look at. But of course I also look at the normal weather forecast – are there any sun symbols at all or is it going to rain that day? That can rule out a lot of days. Then I sometimes look at Paraglidable to get a rough overview. Which days can be good and which regions, but XC Therm also provides a lot of information. And when it comes to a flying day, I look at the details, i.e. the exact thermal forecast for the day and the wind at different heights. I usually do this with Windy. Now there’s a new weather site, wetter.aero, which I’d like to try out. It’s similar to Meteo Parapente but as a free version. However, I haven’t yet been able to test how good the forecast really is.

Ad Nubes: Which weather model do you use?

Ulrich: I usually switch to ICON-D2. But sometimes I also look at several, so typically ECMWF is preset and then I switch to ICON-D2. If the wind is marginal and I really want to fly, then I look at the GFS. It often has the least wind, but of course I trust the most accurate one the most.

Ad Nubes: This is ICON-D2. It has the highest resolution, so I usually look at that too.

Ulrich: When I look at it, I mainly want to see the supra-regional wind. I’m not so interested in the point forecast, which can be completely different at any location. But what you can see very clearly is where the basic current is coming from and from which direction the wind is flowing around the Alps. Sometimes you can even see foehn effects, where much stronger winds blow through the foehn valleys. That would be a clear sign.

Start preparation

Ad Nubes: Right, let’s move on to the topic of launch preparation, do you look at the NOTAMs? And, if so, how?

Ulrich: To be honest, I rarely look at them. I know you should do that more often. I have an app on it called notam.info or something like that.

Ad Nubes: In principle, this is also quite good, it just has the problem that it directly excludes any guarantees in its terms and conditions. You can use it, but there’s no guarantee, so it might fall by the wayside.

Ulrich: I know. But even for complicated things like that, I prefer to look at the airspaces on XC-Track, for example. I know that’s not the official information, but it’s well visualised. It’s usually the case that the airspaces that really affect us, i.e. some zone that is set up temporarily, are also well described on DHV and other platforms, and so far I’ve always been able to understand it quite well.

Ad Nubes: What else do you check when you’re at the launch site? Do you check the weather stations in the area, for example, or do you just trust your intuition and fly off?

Ulrich: It depends very much on what kind of weather is forecast. On a day when no particular danger is forecast, I only pay attention to the take-off wind and potential updrafts. It’s different if, for example, a foehn wind has been forecast. Then, of course, it always depends on which launch site you are at, so you can often still fly at Brauneck, for example. Then I look at the wind values on the Patscherkofel, as many people do. And so there are different things I look out for in every type of weather situation. For example, it’s often the case that rain can come at some point or even thunderstorms. They don’t usually appear directly at the launch site first, but typically move in from the north-west. Then I keep checking the rain radar throughout the day, even in flight. How far away is it? Is it dangerous or not yet?

Ad Nubes: In the XC-Track you can now look at rain areas. Have you activated that?

Ulrich: Yes, it’s active. I zoom the map out that far, 100 kilometres if necessary, to see if it’s still far enough away.

Ad Nubes: In flying, it’s common to have a checklist. Do you do that, do you work through a checklist?

Ulrich: Yes, I actually have several checklists. When I take off, I do what you learn in flight school. This 5-point check. But I have lots of checklists for myself, basically before I even set off, so that I’ve packed all my things together and what I need to look out for. I have a checklist here on the XC track itself for everything I need to think about. This concerns myself and my equipment. For example, putting the elastic in my shoe, switching on the XCTracer or putting on the Uri and taking it out of the harness. Everything I’ve ever forgotten is basically on there.

Ad Nubes: I’ve forgotten all sorts of things too, from vario to gloves, which gets really embarrassing when you want to fly in colder conditions and you’ve forgotten your gloves.

Start

Ad Nubes: So what do you base your launch decision on? So if, let’s say, you’re already prepared, you’re standing at the launch site, you’ve spread out your paraglider. How do you make your city decision?

Ulrich: The question now is about the earliest time you can launch.

Ad Nubes: Right and in the direction of the thermal indicator.

Ulrich: It’s incredibly difficult to catch such a time. And what I’ve actually learnt is that even the top pilots don’t know exactly. I feel the same way. I try to pin it down to certain indicators. If I see three canopies open in front of me, then I know it’s possible. It’s so obvious and clear to everyone. If I see a flock of birds rising relatively quickly in front of me, then that’s enough, that’s also pretty good. But the time in between is incredibly difficult to recognise whether it’s enough or not. And if you want to catch the earliest possible moment, then you have to accept that you can also be at the bottom.

Ad Nubes: You’re not necessarily the early bird now, but you’re already waiting. Let’s say if there are students or other early starters on the road, do you wait for them or do you say I’m happy to take the risk?

Ulrich: Normally I like to see someone who can turn up before me on the really big routes, for example on the Grente, it’s always the case that someone starts so early that you can wait for them. If there aren’t that many people on the mountain, I’m sometimes the first to start. Especially on days when I’m quite sure, I know the forecast and it already indicates thermals. Then I sometimes go out without seeing any indicators. That has usually worked.

Ad Nubes: But there are times when you’ve gone down, even directly after take-off.

Ulrich: That does happen sometimes. It happens especially on days when it’s not clear whether there will be any decent thermals at all.

Ad Nubes: What would you say, is XC-Therm already relatively reliable or fifty-fifty?

Ulrich: In what respect?

Ad Nubes: Yes, are the thermal predictions that the tool makes correct? Let’s say in terms of thermal catch, base height, thermal strength, things like that. I mean, you won’t have collected any statistics, but in terms of feel it’s pi times thumbs or are you saying it’s still relatively unreliable?

Ulrich: Well, it often comes close. But you have to estimate the numbers somehow. In Bassano it’s often the case that you get very weak thermals in spring or almost in winter. And in reality you have days with mega thermals. You need some experience to be able to judge these values. That’s why I switch back and forth between all these tools, because I now have a certain amount of experience with XC-Therm and can roughly say that if the diagram looks like this or that, then it will probably be a really good day. Or if it looks like this or that, then there are some faults in it. I don’t think you can ever transfer this forecast 1 to 1. But on good days they fit more often than on bad days and on good days it’s most important.

Flying

Ad Nubes: Let’s talk about flying. Every normal pilot also observes the weather. That should be the case, and you probably do too. What do you pay attention to when flying, weather-wise?

Ulrich: There are basically two aspects to it. One is to avert danger, so that I don’t get into any bad situations. Above all, observing clouds and how big they grow on days when it can be dangerous. Of course, I always keep an eye on that. If the day is forecast to bring thunderstorms or overdevelopment, I keep a very close eye on that and don’t fly to the larger clouds.

The other thing is of course the observation for successful flying. Where is the best line or where can you expect something good or where is perhaps an area that doesn’t work at all? Of course, I also keep an eye on this all the time, as far as possible. It’s not always easy to recognise. One example is when you have good cumuli all over the area and there’s a blue sky where you’re about to fly over. That’s a signal that something is probably wrong. And then you have to come up with a theory. What could be the reason? Does it affect me now or does it not actually affect me? And adjust your flight planning accordingly.

Ad Nubes: Do you only fly in the Alps or do you also fly in the lowlands?

Ulrich: I also fly in the lowlands sometimes. For example, I flew a few laps of Chiemsee. In Colombia, you always fly both mountains and lowlands, so that’s all right. But I haven’t done any long one-way routes yet.

Ad Nubes: So you always try to fly triangles or flat triangles or there and back, something like that.

Ulrich: Exactly, so far I have. Whenever I get the chance, I like to try it. There were one or two days this year where people flew long one-way routes from the Alps to the lowlands. If I ever get the chance, I’ll do that too.

Ad Nubes: Like Georg, he flew almost a little bit to Würzburg from Brauneck. That was 260 to 270 kilometres, which is pretty impressive.

Do you look at the weather stations when you’re flying, you could get the idea of looking at the weather stations in the surrounding area or having them displayed on your smartphone. Is that something you do?

Ulrich: I’ve done it occasionally, whenever I ask myself whether the wind might be too strong, but it’s not always easy to check. You have to know the stations that are in the area to be able to assess this and then switch back and forth a lot on your mobile phone. I don’t have this directly in the flight computer, but go to a website and have to click back and forth, which isn’t always so easy.

Ad Nubes: Well, I know the website winds.mobi and it shows various wind stations in the area, which is quite helpful, but I haven’t used it in flight either. Have you activated the wind display in XC-Track?

Ulrich: Which one do you mean?

Ad Nubes: It is calculated in XC-Track.

Ulrich: I have the wind speed, which is calculated. And I have the wind speed over altitude. You usually fly with a different wind than the one you land in. This means that you don’t normally have an indicator before landing and this is usually the most important, so when it gets dangerous, the wind has to be right at the bottom.

Ad Nubes: Have you ever had a situation where you expected to have too strong a valley wind to land, so you preferred to land somewhere on the mountain?

Ulrich: Not really. I had a situation with very strong winds on the ground in Colombia. There was the strong Pacifico wind, which is relatively strong every day and if you’re somehow travelling at 25 to 35 km/h, that’s not a problem, it’s completely normal. And that day it was certainly over 50 km/h, I had a very high altitude, even at the end I could see all my fellow pilots going backwards, it was announced on the radio and it was clear that it was going to be a difficult landing.

Ad Nubes: Speaking of radio. Do you fly with a normal PMR radio or what do you have with you? Have you ever tried out Zello?

Ulrich: I have the equipment for Zello, but I’ve never been able to try it out in flight. That’s mainly because I don’t have a counterpart who’s doing it now. But it seems to be spreading more and more in the scene. So maybe someone will come along soon. So far I use a PMR radio on all longer flights.

Ad Nubes: I bought a Bluetooth transmit button, haven’t tested it yet either. Philipp Reiser said it works quite well, he doesn’t need a headset either, he practically talks directly into the smartphone and it seems to work quite well.

Ulrich: I have this Shokz headset that you put round the back of your ears. Some people say that it works quite well. But as I said, I haven’t got round to using it in flight yet.

Ad Nubes: Has it ever happened to you that you’ve had to fly around rainy areas or even thunderstorms somehow? Or haven’t you had such situations yet?

Ulrich: It has already happened to me that I felt I was too close to a thunderstorm, where I then clearly said to myself afterwards that I would please avoid it next time.

Ad Nubes: Have you really had thunderstorms in the immediate vicinity where you said, that could have ended badly now?

Ulrich: Yes, I’ve had thunderstorms that were far too close to me. Of course, you don’t know whether it could have turned out badly. I’ve never felt it in the sense that I’ve been blown upwind or anything like that. But yes, if lightning strikes the mountain somewhere next to you, then it was too close.

Ad Nubes: There’s a recent case in India. Someone got caught in a thunderstorm and was somehow pulled up to 7400 metres.

Ulrich: He was more lucky than good that he survived. It’s really nothing to joke about. I saw the track too. It looks insane in Google Earth when you look at the track. Firstly, how quickly he went up and then how quickly he came down again. That’s not an experience I want to have.

Ad Nubes: Do you usually fly alone or in a team?

Ulrich: For cross-country flights, whenever possible, I like to fly in a team. It’s not always possible to stay together or to have the same speed as someone else, but you definitely have big advantages in a team and I always try to do that when possible.

Ad Nubes: You guys have been insanely lucky in Colombia. You and Dimi, I added up your distances, the XC kilometres you flew in the two weeks, that was 1705 kilometres. Amazing, you really are a great team. Did you mostly fly together?

Ulrich: We flew a lot together, more at the end than at the beginning. But in Colombia you always have a lot of pilots around you. You’re not so reliant on waiting for each other as you might be on other routes. And that’s why things have drifted apart. Later, we often came together again. We have a relatively similar speed over the track and that’s why it works quite well.

Ad Nubes: How do you go about finding thermals? How do you find thermal sources? Do you have any tips?

Ulrich: There are many, many models that you basically work through. The simplest is Vogel’s triangle theory, i.e. the sun warms the slopes and then the thermals sweep up somewhere. For the pilot, this means that I fly up the slope until I reach one of these ridges and then fly along this ridge down into the valley. And then you normally catch the thermals.

Ad Nubes: You fly relatively close to the slope and at the ridge you fly out towards the centre of the valley and hope for thermals.

Ulrich: Exactly, that’s typical. Of course, I still look at how the terrain is orientated, where the wind is. And above all, where is there a cloud overhead. That also makes a big difference and of course it has a lot to do with when I have to turn up? So at the point where I still have plenty of height and when more and more ridges appear, then I don’t have to take a weak climb with me. Then I just keep flying in the direction I want to go. And I’ll find something later. But the search for thermals has many aspects, depending on how the air is and how everything feels. That’s just the simplest theory and in other situations I search in a completely different way.

Ad Nubes: I’ve often made the mistake of searching too close to the slope, especially in stronger winds, and I’ve always wondered why the hell there’s no upwind? For some time now I’ve been flying a bit further away from the slope and I often find the thermals there.

Ulrich: There are different theories that take effect at some point. So what you describe with a little further away from the slope can be that the slope bends somewhere and then continues normally further back. Then the thermal breaks off at the kink and so there are no more thermals further back. Or there is the effect that you have this invisible mountain. I don’t know if this theory means anything to you?

Ad Nubes: No

Ulrich: So normally we always have wind in some form and typically you actually pick a mountain where the wind is actually head-on. If it gets a bit stronger, then the wind has to flow around this mountain. And then there is often an air mass in front of the mountain that is relatively stationary because the wind has to flow around it sideways. In other words, the air doesn’t go off to the side directly in front of the mountain, but there is an air parcel in front of it and that is this invisible mountain and the thermals often pull up on it. That’s why you have very strange effects, because the thermals are not directly on the slope, but sometimes much further out.

Ad Nubes: Well, I think Lucian has his own theories about that too. He’s practically looking for convergences on the slope, but that doesn’t sound like a good idea right now.

Ulrich: I think the theories are all correct, but they don’t all work in the same way at all times, sometimes one delivers a good result and sometimes the other. And a very important point is always that you can stay in the thermal. I think that’s also the bigger problem for many people. From my point of view, it’s important to stay upwind. Most people I see turn far too slowly, for one thing.

Ad nubes: What does turning too slowly mean?

Ulrich: That they turn far too big circles. And you see a lot of them falling out of the thermal on the leeward side. So that’s a typical effect, we’re talking about the fact that there’s always wind somewhere. The thermal on the windward side is typically the strongest, and then there are other climb cores that go up a little slower, they go up a little more offset on the lee side. And if you shimmy up in one of these beards that’s a bit further downwind, you won’t get quite as high.

Ad Nubes: To what extent does the thermal assistant in the XC track help you there. Is it a help for you when searching for thermals?

Ulrich: Actually, only when I’ve fallen out completely, that I simply fly back to where the thermal indicates. When I’m circling, I practically don’t look at it at all, so I rely more on my own feeling, because that’s more accurate than the display.

Ad Nubes: I also have mixed experiences with the thermal assistant, in that it sometimes works if you have lost the thermal and then look to see where the thermal is so that you can go back and actually find it again. But there are also many times when you can no longer find the thermal where the thermal assistant shows it.

Ulrich: If you are exactly at that point and the thermal is no longer there, then you know that you can definitely continue flying.

Ad Nubes: What else is there to say about the flying tactics you use? Do you have any special tips for us?

Ulrich: Flight tactics is a very broad field. What exactly do you mean by that?

Ad Nubes: Yes, let’s say you’re having a good thermal day. When do you ignore the thermals? When do you hope to find even better thermals?

Ulrich: When you’re just looking for thermals, it’s a matter of feeling. It depends a lot on what’s in front of me, how many chances I still have, how high I am. How many other people can I see right now, so if I see someone in front of me turning up very quickly, then I don’t take a weak climb with me anymore. But there’s no general rule that I can apply. In terms of tactics, I’ve decided a few times this year not to take the first line. You have live tracking, you can always see the other pilots and it was often the case that I was out relatively quickly at the start and flew well. But that’s not always an advantage, because then you’re also the first at the turning point. You always run the risk of missing something or not making good progress somewhere, while the others can see everything from behind. And I actually took myself back a few times so that I didn’t fly somewhere alone and leave others in front. And yes, if you do this at the right time, it’s a great advantage. Even on my longest flight from the Staller Sattel, I could see exactly how one after the other dropped off in Lüsen in the live tracking. And then I had time to think, what do you do now? Do I do exactly the same thing with possibly the same result or do I try to fly somewhere else that I’ve never been before? And that was successful.

Ad Nubes: With XC-Track you can set the chase mode so that you simply follow good pilots, the same line that your colleagues are flying, so to speak. Do you do that too?

Ulrich: Yes, I always set 2, 3, 4 pilots at the start of the flight, usually the friends I’m travelling with, so that I simply know where they are. Otherwise they get lost in the live tracking. The line itself isn’t that important to me on most flights, because I already know where I’m going. Where the circles are there was obviously a thermal. It’s a very good indicator.

Ad Nubes: What do you think of the speed command theory? Is the speed command theory something that you actually apply?

Ulrich: I use it to the extent that I try to optimise my speed. But I can’t calculate that in flight. I look at my glide ratio and if it goes below 7 or so, then I hit the accelerator.

Ad Nubes: So you often fly at full throttle, not only when crossing valleys, but also when flying on a slope?

Ulrich: More often than not, yes. If it gets too turbulent at some point, then of course I go out again. But I feel very comfortable with the Trango X and like to go full throttle.

Ad Nubes: Don’t you fly according to the motto, I’m now sinking 2 metres, now I give half throttle, at 3 metres sink I give full throttle and then you have to take the tailwind or headwind into account, which makes it very complicated.

Gliders even fly according to McGrady. That makes it even more complicated than for us. But it’s all just theory, I think it’s best to fly by feel, or do you see it differently? I’ve never really done the maths.

Ulrich: I do it by feel because, as you say, there are many parameters that play a role, including altitude. What height do I have, how safely do I actually get there, that’s usually the more important point. But if you have a 3 metre drop, then you can normally always pedal fully into it, or if you have a strong headwind, then basically you can. And if there’s nothing else to prevent it, such as really strong turbulence, then I just kick in and so the theory isn’t actually that difficult.

Landing

Ad Nubes: Landing issue. You don’t come back to the official landing site. What do you look out for when you make an off-field landing?

Ulrich: Firstly, I need an area that is big enough. Then, if possible, there shouldn’t be any cables or other things hanging over it. And then, of course, in a region where the wind isn’t too bad, i.e. where the wind isn’t likely to be totally turbulent, not in some very narrow spot in the valley.

Ad Nubes: You fly in such a way that you can get over unlandable regions with your current glide ratio and of course add a safety margin.

Ulrich: Yes, exactly, so I do have cases where you can no longer see the landing site, in Bassano for example, where I then somehow only have a very small option as a landing site, which is not nice. But I don’t fly any further without a landing site.

Ad Nubes: I asked you earlier, you’ve never landed on a mountain because you’ve been in a situation where maybe the valley wind is too strong.

Ulrich: I have made landings on the mountain, but not because the wind would otherwise have been too strong.

Debriefing

Ad Nubes: I find the reports you write on the DHV-XC particularly interesting, very few of us do that. I think it’s good that you write such a detailed report. Do you do it just for yourself or to learn something new or to analyse mistakes you may have made?

Ulrich: I mainly write the reports for myself because I know that not many people look at them. I like to read through them again, especially in winter. Then I just look over the flights I’ve had and look at the photos, read through them and the DHV site is good for that. I have confidence that it will stay that way for a few more years. And of course, a few other people now also read it and give positive feedback from time to time. That’s certainly another reason why I’m happy to keep doing it. But first and foremost, I do it for myself.

Ad Nubes: I like it, I enjoy reading your reports. What’s particularly striking about you is that you always take a selfie with your big grin.

Is there anything else to say about debriefing? Maybe something about lessons learnt?

Ulrich: I have a huge list of things that I want to improve and have already improved when flying. So many of them have already been ticked off. And every time I realise something has gone wrong, be it with the equipment, the tactics or something else, I write it down. I want to try this or I want to change that. And over the years, I’ve accumulated quite a lot, which is of course completely specific to me. Put the information on your display, restart the mobile phone once before the flight because I had problems with it. Or putting the elasticated strap in my shoe because I forgot to do it and things like that go into completely different areas with the equipment. I think there are now well over 100 points that I’ve collected and ticked off at some point. And it’s still growing, of course.

Ad Nubes: What’s striking about you is that you’re someone who owns up to your mistakes and always uploads them. I don’t know if you do that for all your flights, but you do upload short flights from time to time. That’s also a special feature that should be mentioned.

Ulrich: I still think that’s right, because even the short flights are nice flights. You get a bit spoilt over the years that you can fly so far and so long and that it often works out. But of course that’s not always the case. Especially now that we’re heading towards winter, I realise how valuable it is to get up in the air at all. And on the other hand, it’s also good for the people who watch it and want to fly far, that they don’t forget that the top pilots are also regularly on the ground. It’s not just me, but many others too.

Risk management

Ad Nubes: Risk management. I think safety is also a big issue for you. What can you tell us about that?

Ulrich: I think it’s important that everyone can assess their abilities and, as we discussed at the beginning, I know that I’m a bit behind when it comes to acro manoeuvres or SIV topics, for example. That’s why I have to accept that I’ll turn around a little earlier or finish a little earlier or maybe not go to CCC in the equipment. That’s what I’ve decided for myself, I’m not going to do that at the moment at least. And I think that puts me in a pretty good risk zone. So far I’ve been flying accident-free for 14 or 15 years.

Ad Nubes: But you’ve never had a situation where you say you were more lucky than good, in this situation I was overwhelmed.

Ulrich: Not in that sense. I have had situations where I was overwhelmed. Especially in the past, but less so in recent years. I wouldn’t say that I was more lucky than good. I’ve had situations, for example in Colombia, where I probably tore my glider off, it shot forwards and then collapsed heavily. That resulted in a spiral dive with SAT, I was quite overwhelmed at that moment. But that was at an altitude of almost 3000 metres, where you still had a lot of time to straighten it out and I managed to do that. So I had a few points like that, although not many. The risk wasn’t far too high, but I simply behaved wrongly in the situation. And things have got better in the meantime. The frequency of dangerous things happening to me is very low and I’d like it to stay that way.

Flying in a team

Ad Nubes: You did a great flight from the Löffelstein and wrote a detailed report about it. Is there anything else you would like to say about it? That was quite an extraordinary flight you did. Was it 250 or 260 kilometres?

Ulrich: It was 242 kilometres and for me it was the furthest so far. If you compare that with the records, it’s still way up there.

But the conditions in 2024 were difficult. That day wasn’t incredibly good either. But it was probably the best day of the year. That doesn’t mean that much and I know that I could have done a lot more. On the one hand, I wasted a lot of time at the Staller Sattel on the way back due to a wrong decision and later the day also became difficult, for example we struggled for a long time at Lüsen. Especially towards the end in the Dolomites, where almost everyone was on the ground, only Ramona and I made it through. And we are now the two of us who are pretty high up in the rankings.

Ad Nubes: Ramona flew away from you at the start, where you made the mistake at the beginning. Did you catch up again later or how did it happen?

Ulrich: I think Ramona started late, as usual. At first I had a bigger lead. I don’t know exactly when she overtook me, but probably on the way back over the Staller Sattel. And then I followed the field to some extent and ultimately had an advantage because I was later in Lüsen. That meant I could see what was happening ahead of me and possibly also because the day opened up again at the back. There was probably a phase where there was a lot of shade, that was exactly the moment when many were at the bottom. And that was probably my luck that I got to the Dolos a bit later.

Ad Nubes: Maybe you would have gone stale in that situation too.

Ulrich: Exactly. If I had been one of the first to fly the standard route, I probably would have.

Ad Nubes: In Colombia you flew a lot with Dimi and here with Ramona. Which other XC luminaries do you fly with?

Ulrich: This year I flew a lot with Florian Manteuffel.

Ad Nubes: I haven’t noticed him on the DHV-XC yet.

Ulrich: He’s a good competition pilot. But otherwise Dimi is the main wingman, also because we often go on flying holidays together. In the air, of course, it changes from time to time.

Ad Nubes: Are you planning to fly to Colombia again next year.

Ulrich: That is still to be decided. At the moment I could well imagine it, but nothing has been finalised yet.

Ad Nubes: Have you had much luck this year with El Nino or can we expect good flying weather again early next year?

Ulrich: It won’t be like that again, I don’t think so. I’ve been to Colombia twice, once in 2020 and it was very good then too, we were able to fly really well, but it was nothing like 2024 and I don’t think it will happen again so quickly. Of course, there are advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the conditions were perfect for good cross-country flights. But it was also relatively tough, the days were exhausting and there were a surprising number of people who hurt themselves or were overtaxed.

Ad Nubes: Really, were there any accidents?

Ulrich: Of course. One thing always comes with the other.

Ad Nubes: The longest flight was 160.

Ulrich: I think I had a 175, but not completely closed after XContest.

Other, goals

Ad Nubes: You’re quite keen on cross-country flying. Is competition flying an option for you?

Ulrich: I can understand why people like to do it. For me, it doesn’t really fit into my life plan. For one thing, I’m self-employed and can rarely plan so far in advance. Competition pilots have to reserve 20 days of holiday at the beginning of the year just for competitions. And it’s not really compatible with my family. Maybe that will change later. But at the moment I’m very happy with XC flying and it simply suits my life better.

Ad Nubes: Is hike and fly something for you?

Ulrich: I basically do it out of necessity, because you fly the long distances from the mountains where you have to walk up.

Ad Nubes: For example?

Ulrich: The Grente or Staller Sattel. I also like to go up a mountain in autumn. Of course, my equipment is not at all suitable for this. But of course I like doing it, just not as a competition.

Ad Nubes: We’ve already briefly touched on acro flying, is that not an option for you at the moment or could it become something in the future?

Ulrich: I would like to improve my skills in that direction. I’m not going to become a really strong acro pilot, but I’d like to be able to fly over the lake and a stall from time to time.

Ad Nubes: If you’re thinking of switching to the 2 Leiner, the requirements will be higher. I can’t judge, but things like backfly and stall and so on should be well mastered. What plans and goals do you have for next year or for the next few years apart from cross-country flying?

Ulrich: So far, I’ve never set myself any specific goals. I actually want to keep going to places where it flies particularly well and then get the maximum out of it. But I’ve never set myself a specific goal in the form of a ranking or kilometres.

Ad Nubes: Did you ever fly 300 kilometres before, you did the 240? Then 300 kilometres would be the next mark.

Ulrich: I would love to achieve that. I don’t know if that’s realistic, because you have to have a very high average speed. A speed average of just under 30 km/h, otherwise it won’t be possible. And I’m not fast at the moment. Except on extremely good days, when it’s almost over-developing. If the opportunity arises, I’ll take it with me. But I’m not planning on it. I wouldn’t be disappointed if it didn’t work out.

Thermal Map

Ad Nubes: Then we come to the last topic. Your development, or you did it together with a colleague, the thermal map. You’ve already reported on it in detail with Lucian, but it was still relatively early days, still in the testing phase. I think that was in 2021, when he did the podcast with you. What’s your experience with the Thermal Map since then?

Ulrich: I started the Thermal Map while I was without a project. And I pushed it as far as I basically had at the time of the podcast. So it didn’t get much further than that because I was working normally again and didn’t have the time for it. I’m still very happy with the map because it still helps me. The biggest help was that I learnt faster. With fewer attempts, I realised where the points are where the thermals typically come up. If I no longer have any idea where the thermals might be, I look at the map and fly there. There’s usually something right there. Except on days when the wind situation is difficult, for example. Then you have to mentally shift all the points a bit. So I do believe that it has helped me. And I also believe that it can help other people.

Ad Nubes: I haven’t used it that much yet, but have firmly resolved to use it more next season.

Ulrich: For me, the order is clear: you first look at what you see in reality. So, where are the other pilots, where are the clouds? The first priority is to fly off that and your own experience is the next thing to come. If I know that it typically always goes up right at the corner, then I fly to it. But that will then also correspond with the map. Only then, if I don’t have an idea, if the day is somehow difficult or if it somehow doesn’t go up, then I look at it again and then have another idea. Or also at points to know exactly how big the range is where it could go up. If I unexpectedly still have no climb, then I look at the map and possibly see that there could be another 300 metres of updraft. That’s information you wouldn’t otherwise have. That’s already an advantage.

Ad Nubes: Have you updated the map since 2021? So you’ve retrieved new data from the DHV-XC and also from the French database?

Ulrich: Not really any more. That’s something I might do this winter. There are a lot of data sources that you could still tap into. The DHV site has changed since then and I would have to update it. The most important thing would be the XContest data. That’s a lot more. However, the developers are doing a pretty good job of making that difficult.

Ad Nubes: But maybe you’re planning to do something in that direction this winter?

Ulrich: Yes, I may well do another update or other calculations. Depending on how things work out time-wise.

Ad Nubes: What do you mean by other calculations?

Ulrich: At the moment, the map only shows the thermal spots. You could also consider other things, e.g. which line choice is the best. But I have to experiment with what makes sense in what form. And what the data provides.

Ad Nubes: That would also have been one of the questions. So you haven’t done anything like that yet?

Ulrich: Exactly. I haven’t done anything else yet, but it’s definitely interesting. You have to isolate the relevant information and present it appropriately. How do you extract that from the data? For example, I believe that there are certain regularities for load-bearing lines, but what do they depend on? For example, if we have a 20 km/h northerly wind, the load-bearing line will probably be somewhere else than at 5 km/h. But then you would first have to analyse these laws. But then you would first have to find out these regularities. Perhaps an AI could do this automatically. In any case, it’s not easy because if you just put the data on a map, you probably won’t get a meaningful display.

Ad Nubes: Artificial intelligence has not yet been integrated or taken into account.

Ulrich: Exactly.

Ad Nubes: Good, then I’m actually done with my topics. Is there anything else you’d like to say or topics that I’ve forgotten?

Ulrich: I can’t think of much directly. You’ve already touched on a lot of topics.

Ad Nubes: Thank you very much for agreeing to do the interview with me. It was fun talking to you.

Ulrich: Thank you very much for taking the time and trouble to do interviews.

Links to the interview

Ulrichs Homepage about the Thermal Map

Ulrich’s 242 km flight from Löffelstein with detailed report

Podcast with Ulrich Podz-Glidz #55: Thermal Map

Video with Vogel’s triangle theory

Dimi: XC GUIDE: How to fly a 120 km triangle in Bassano with a paraglider