In this article I have already reported on the rescue throw training, which is organized and carried out by Bodenlos e.V.. But training without learning something from it doesn’t really make sense. That’s why I’ve summarized here once again the findings described by my club colleagues in the club’s internal forum, most of whose texts I have taken over from the original. I have supplemented the texts with my own findings.

Update 7.6.2024: Add answer of Bergrettung Tirol.

Rescue throw, tree landing and the risk of suspension trauma

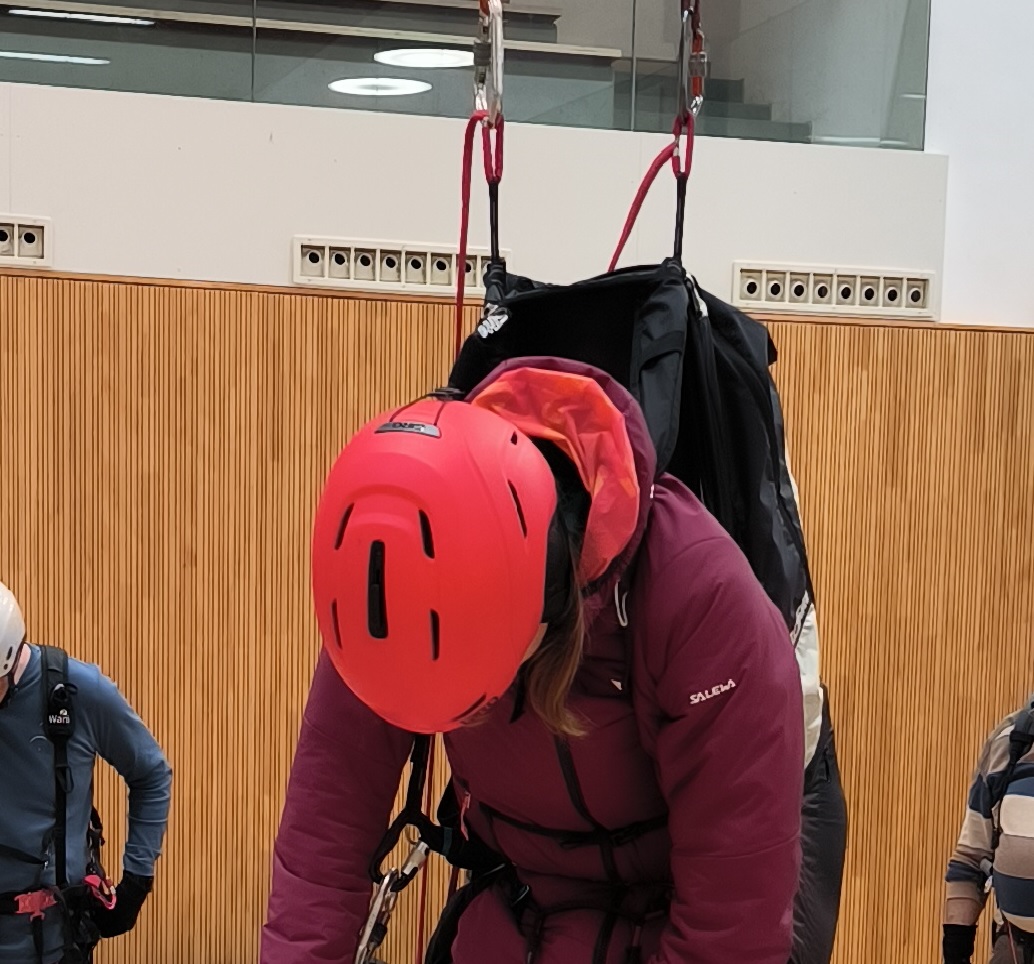

Unfortunately, it is a common scenario for paragliders to be caught in a tree after a rescue throw. As the rescue suspension is attached to the back of the pilot, the pilot often remains in the position shown in the photo.

The result of the position shown can be suspension trauma. The term suspension trauma describes a life-threatening state of shock that can occur if you hang motionless in a harness system for a long period of time. The forced upright posture causes the blood to “sink” into hanging parts of the body due to gravity (source: Wikipedia German). The situation is exacerbated by the constriction of the legs, not to mention the pain, especially for men.

The first symptoms of the trauma, such as paleness, sweating, dizziness, etc., can appear after just 20 minutes. Either you lose consciousness and risk your life, or you try to free yourself from the situation and put yourself at risk of falling. There are known cases in which such falls have led to serious injuries or even death.

Webbing sling for standing

It is recommended that you take a sling with a carabiner that is suitable for your harness and leg length. The carabiners can be hooked into the main carabiners in order to gain a foothold in the sling. The setup should definitely be tested in advance to ensure that the length of the sling fits your body proportions.

In my case, a 240 cm long sling and two 8 kN carabiners (which are not approved for climbing).

One pilot suggested tying the speed bar to the carabiner and using it as an additional belay. However, there are concerns that this is much more complicated than the webbing sling solution with a carabiner. At the same time, it serves as a backup in case the first method does not work for various reasons (for example, if the sling has to be used elsewhere for belaying). However, it is important to test this method extensively beforehand, as not every speed bar, especially with very light models, is designed for the weight of an adult and could break. This would be an extremely unpleasant surprise in the event of a tree landing.

Securing to the tree

Pilots are advised to carry a second sling to secure themselves to the tree to prevent a potential fall if the rescue operation fails or the branch they are hanging from breaks. It is important to note that short slings, such as those used for climbing, are not sufficient. Instead, the same type of webbing sling used for belaying should be used.

Make yourself noticed!

After half an hour in the air, you may be hoarse and your call will go unheard. So don’t be a whistle, but use one to make yourself heard. The loud and piercing sound of a whistle can be heard much further than your voice, does not use up valuable energy and minimizes the time you spend in the air until you are safely back on the ground.

Opening canvas locks

Who hasn’t heard of the horror stories of the rescue services ruthlessly cutting all the lines to get the glider out of the tree (this is not an accusation against the rescue services, who often work on a voluntary basis). To prevent this, it is advisable to take a suitable open-end wrench with you so that you can ask yourself or the rescue workers to open the line locks with the open-end wrench if necessary. But of course, your own health comes first and you should not open the line locks if there is a risk of falling from your current position.

I have fitted the open-end wrench with a rubber cord to prevent it from falling. If you have soft links on your glider, you should find out in advance how to open them.

Rescue cord – necessary or not?

For a long time, the DHV (Deutsche Hängegleiter Verband) made it mandatory to take a rescue line with you, but now it is only a recommendation. In the event of a tree landing, you need a rescue line to pull a rope or other rescue objects up to you. However, I have since heard that the rescue services do not rely on this.

The Bergrettung Tirol replied to my enquiry on the subject as follows (translated from german): ‘We usually have tree crampons, so we can also climb up bare trees. In this respect, it is possible for us to get up to you without a lifeline. But it still makes sense, as you are all the quicker if you can pull up a rope. In this respect, I can follow the recommendation. However, should an accident happen and you don’t have a lifeline with you, we still have the means to get up to you.”

Where did you stow the things?

You may not be able to reach many of the pockets that are perfectly accessible in flight when hanging. Zippers can no longer be opened and if you do manage to get something out, other things fall out and then lie 15 meters below you. We’ve seen it all. Think about where you stow your things. The same goes for your phone. Some people think about getting a cockpit or a fanny pack.

I got myself a toiletry bag that just fits in the pocket of the leg bag. The advantage of the toiletry bag is that all the accessories are stored in a reasonably organized way. In addition to the items described above, I also have a first aid kit in the toiletry bag.

Water landings and lines that tie you up

Anyone who has ever thrown the rescuer in the SIV knows how quickly you are tied up in the water by the lines. This is even more serious in a current. Get yourself a line knife and attach it to your chest strap (or something similarly easily accessible). Years ago, a club member tested various knives and recommended the Mystic Knife. It also cuts through shoulder straps if necessary.

Velcro components in the rescue system

On some harnesses, the Velcro components in the rescue system were difficult to open. The longer the Velcro is closed, the stronger the cohesion becomes. Velcro components in the rescue system should therefore be opened and closed regularly so that they open as intended in the event of a rescue throw.

Where is my rescue handle?

For some participants, the rescue deployment took a very long time. You should be aware that speed can save your own life, e.g. if you have to throw the reserve close to the ground or the glider is in autorotation. Delayed deployment of the reserve is often due to taking too long to find or grasp the reserve handle. This can have two causes:

- Grip in the wrong place

- Rescuer handle (with gloves) difficult to grasp

Gripping the right place can be practiced on every flight: Reach downwards from the carabiner as a landmark towards the rescue handle. With regular training, this becomes part of your muscle memory so that it can be found more quickly in the event of a rescue release.

If the rescue handle is difficult to grasp, you can check whether the manufacturer has an updated version (this was probably the case with a harness)

The useless support reflex

When looking through photos, it was noticeable that many participants tried to support themselves with the brake in their other hand when reaching for the rescue. Even if the simulated situation of immediately reaching for the rescue after the collapse is not entirely realistic, the reaction to the one-sided tipping of the harness is. This reaction is instinctive – from an early age we learn to support ourselves when we lose our balance. However, this support reflex is not helpful in the air. It can even make the situation worse and lead to a cascade (one-sided stall).

In the air, it is important to fly the glider. In most situations, this does not involve braking inputs to the very bottom, especially no longer than is the case with the bracing reflex – there are of course exceptions such as catching a strongly shooting wing. It is important to rely on your harness, keep as cool a head as possible and fly the glider actively. For wings with a high level of passive safety, the reaction “hands up” is better in most situations than strong (one-sided) braking.

Being able to work on this starts with being aware of when you are doing this in the first place. The support reflex can then be counteracted by training in a simulator, as in rescue throw training, as well as through visualization.

The points listed above are well summarized in the first two of Flyeo’s “4 Fundamentals”:

Trust your harness

Trusting your harness means to use your harness as it was designed. It is the foundation of the fundamentals and until dealt with you will find it almost impossible to gain all of the other skills.

Imagine a rally car driver sitting on one of those large inflatable exercise balls instead of a bucket seat, as they speed around corners they are going to loose their balance and try to grab something to regain their balance. They are going to be using a lot of core strength to maintain their balance and their hands will not be 100% dedicated to steering as they will be trying to use their arms for balancing. Now imagine the same driver strapped firmly into a bucket seat, their balance is taken care of, they are fully supported so can relax their body and their arms are completely free to steer the vehicle. Our paragliding harnesses are exactly the same, the second we tense up and try and sit more upright we lose contact with the harness and our backs are no longer supported. It is then that balance comes in to play and our natural instinct is

to use our arms to balance, which is a big problem for us paraglider pilots as we have the brakes in our hands. By trying to regain balance we can inadvertently pull large amounts of brake, creating a secondary event.

Dissociation of your arms

This goes against our natural instincts, it goes against a skill we have been practicing our whole lives, ever since we took our first steps as toddlers… to fall without putting our arms out. This notion is hard for us humans to overcome as it is so ingrained in us, but it is crucial to piloting a paraglider.

In everyday life if you ever exceed a 30 degree angle your instincts kick in and your arms will come out to catch your fall. We all know the feeling of leaning too far back in a chair and suddenly loosing our balance, your arm will flap around and shoot out to catch your fall.

Unfortunately you will behave exactly the same way when you exceed your tilt angle in flight or when you feel you are loosing your balance. To dissociate our arms becomes far easier when we start to trust our harness, when we are fully supported and know that our harness has got us, we can then let our bodies fall with the knowledge we are safe.