I already explained in an article three years ago that overhead power lines harbour particular dangers for us paraglider pilots. In this article, I would like to go into detail about the construction and route of overhead power lines so that you are able to recognise them from the air and include them in your planning before the flight.

In Germany and, as far as I know, in all European countries, there are overhead lines across all voltage levels, i.e. extra-high, high, medium and low voltage. The structure of the pylons and the cables themselves differs considerably depending on the voltage and the power to be transmitted. Each country and each energy supplier also has its own standards to which the design is subject.

Construction of overhead lines

Even if it is not always easy to recognise the cables in the air, the overhead line masts are quite easy to spot. As soon as pylons are recognised, it can be assumed that they are connected to each other by cables. New overhead lines with newly drawn cables are easier to recognise as the cables still have a silvery sheen. Once the cables reach a certain age, they turn black and are therefore more difficult to recognise against a dark background. If you are flying towards the sun, the opposite is true: new cables are more difficult to recognise.

Overhead lines are generally found mainly in rural areas; in urban areas, at least in northern Europe, only underground cables are generally used. Overhead lines are often laid in a straight line. This also applies to the Alps, where overhead lines are laid across the mountains. There are also branches of overhead lines, or they can suddenly change direction. The pylons are usually set up at equal distances, but can bridge a considerable distance when crossing valleys. Alpine valleys can be literally built up with overhead lines, the Zillertal, mainly around Mayrhofen, is a frightening example. An increased number of overhead lines can be expected in the vicinity of substations, power stations and pumped storage power stations. In southern countries in particular, many overhead lines at low altitudes are to be expected.

The voltage applied to the overhead line can be estimated based on the length of the insulators. Depending on the tension, the ropes themselves and the associated masts have different designs, which are listed below.

As a rule, overhead lines in the extra-high voltage range (380 and 220 kV) have constructions similar to the illustration. The insulators have lengths of 2 to 3 metres. The distances between the cables are around 5 metres. The distances between the cables can therefore be bridged with a paraglider. Often, but not always, the distance to the ground is too great to bridge the distance between the lower rope and the ground. Even if the distance from the ground to the mast is too great to bridge, the rope slack in the centre between the masts can be so small that it can be bridged with a paraglider. This does not include the risk of a flashover.

An earthing cable is attached to the top of the mast for lightning protection. The masts are usually made of steel in Europe, but can also be made of concrete in certain countries.

The construction of high-voltage overhead lines (110 kV) is similar to extra-high voltage, but the length of the insulators is approximately 1 metre. Other statements about extra-high voltage overhead lines also apply to high voltage.

The illustration shows a typical medium-voltage overhead line (10 or 20 kV), here with a transfer to a cable. The length of the insulators is approximately 0.25 m.

Overhead power lines are often found at paraglider landing sites. The overhead line runs so low that it can be bridged to the ground with a paraglider, with fatal consequences for both paraglider and pilot.

The masts can be made of steel, concrete or wood; there is no earthing cable. The distances between the poles are smaller compared to the higher voltages.

Similar to medium-voltage overhead lines, the same applies to overhead lines of long-distance railway lines (15 kV). However, it should be noted here that the tracks are used as a return conductor and therefore the hazard potential is greater compared to other overhead lines. One advantage is that overhead lines can be recognised much better through the track.

Low-voltage overhead lines are becoming increasingly rare as they are being replaced by overhead or underground cables. However, they can still be found in rural areas. They often connect buildings over short distances, but can also be strung across fields, posing a danger to us.

The photo was kindly provided by Heiko.

Before the flight

In order to minimise the probability of a collision with an overhead power line from the outset, it is advisable to find out about possible overhead power lines on the desired flight route. The following options are available:

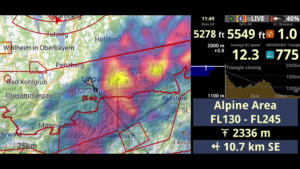

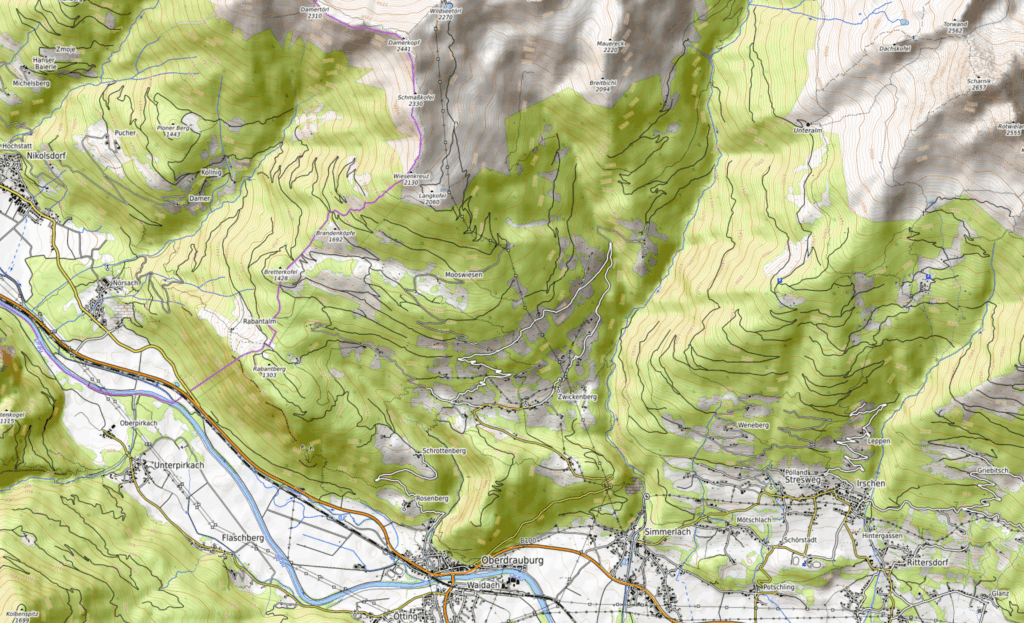

The OpenStreetMap maps show overhead power lines, I use OpenTopoMap for flight planning. In this example, you can see the pilot’s grill in the Drau valley mentioned above. The squares represent the pylons, so the voltage can be estimated: The greater the distance between the masts, the greater the tension.

Overhead power lines are difficult to recognise on Google Earth. In the example, the overhead lines in Mölltal are clearly visible, but probably only because they are relatively new and therefore shine silvery in the sun. The branch over the mountains towards Drautal to Pilotengrill can no longer be recognised, but only the forest aisle gives an idea that there could be an overhead line there.

It is of course advisable to keep the Vario and XC-Track obstacle warnings up to date and activate them in flight to warn of overhead power lines. It is also a good idea to ask local heroes and other experienced pilots about overhead power lines in the flying area.

In flight

The following images were cut out of the videos and are therefore not of good quality. Overhead power lines are of course much easier to recognise in flight.

The photo shows the so-called pilot grill in the Drau Valley near Greifenburg, presumably an extra-high voltage overhead line. It is close to the ground, clearly visible and therefore poses no major danger to us. The only thing it could hinder is the search for thermals close to the slope.

The photo shows a high-voltage overhead power line west of the Brenta. This can certainly make it difficult to find thermals after crossing the valley. However, it is still clearly visible in front of the green forest.

Overhead power lines sometimes run parallel to mountain ranges, as can be seen here in the example from the Zillertal. Here there is a risk of being caught behind the overhead power line when searching for thermals on the slope and, if the height between the mountain and the overhead power line is too low, it is no longer possible to fly towards the centre of the valley.